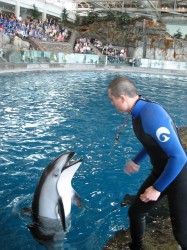

Dolphin trainer for a day at the Shedd Aquarium? Count us in

Does Tim Ward have the coolest job in Chicago? I decided to find out for myself

By Trent Modglin

It didn’t take long. It never does in rare times like this. It was about half an hour after Tim Ward met me at the service entrance of the Shedd Aquarium that I was reminded why I started this magazine in the first place.

Opportunities like this, the ones that make you feel like a kid again, the ones that stay etched into your memory for years, don’t come around very often, so you’ve got to take advantage of them. Thirty minutes after walking through the Shedd Aquarium door, I am standing next to a barking 1,700-pound

sea lion, patting the spongy forehead of a beluga whale and watching streamlined dolphins doing tricks an arm’s length away.

On what should have been a day off for him, Tim instead guides me through part of his normal routine at the Shedd, and serving as his shadow makes me as giddy as the kids on a field trip on the other side of the railing.

I ask him if he has the coolest job in the city. He smiles. “It’s not a bad way to make a living,” he says. “I would say it’s up there.”

Go ahead, be jealous. Not of me, of him. It’s perfectly natural. While you’re sitting in a cramped cubicle going over expense reports, mindlessly daydreaming about that next three-day vacation or how you can’t wait for lunch so you can get out of the office and feel free again, if even for an hour, he’s

having dolphins do flips with a simple hand gesture and getting hundreds of children to oooh and ahhh in the process.

In our version of the real world, the very sight of the exotic animals he works with on a daily basis sends people into a tizzy. They run to the edges of boats and point or pay big dollars for a chance to take a tour or swim in their presence.

It’s not all fun and games though. Tim estimates less than half of his day is actually spent working directly with the animals. The rest, well, that’s not quite as exhilarating. Sorting and cutting up fish in the kitchen and packing it in the storage cooler. Logging, on charts and computers, every detail imaginable about the latest session with one of the animals, a feeding or a health check-up, complete with blood and stool samples. Attending meetings to delegate responsibilities for the day or for the performances, which are all about timing, memorization and execution — both for the dolphins and the trainers. He’s always working ahead, always on the move.

“It’s very much a team-oriented environment,” Tim says. “Preparation is key, and we’re never standing in one place very long. I always compare it to watching ‘ER,’ because there’s so much stuff going on that you could feel lost if you were on the outside looking in.”

These animals are the aquarium’s lifeblood. Their well-being is why the trainers are here, and obviously their biggest concern. And they take it very seriously, right down to the meticulous cleaning. Ah, the cleaning. Everywhere I walk, someone is scrubbing a tank, a bucket or a floor.

“We’re all about sanitation,” Tim says with a laugh, though he didn’t have to, given the heavy scent of the cleaning products in the air. He believes the kitchen used to prepare the day’s food is cleaner than those of a lot of Chicago restaurants, and having walked through it myself during the preparation process, I have no reason to doubt such a statement.

“We’re all about sanitation,” Tim says with a laugh, though he didn’t have to, given the heavy scent of the cleaning products in the air. He believes the kitchen used to prepare the day’s food is cleaner than those of a lot of Chicago restaurants, and having walked through it myself during the preparation process, I have no reason to doubt such a statement.

Our first training visit is with Tyler, a 1,700-pound sea lion. He’s an aging, friendly fellow who doesn’t move as well as he once did because of arthritis in his back hind, and doesn’t see as well as he once did because of cataracts. For that he gets regular eye drops, which has to be quite a sight. Conscious of what Tyler can handle physically in his late 20s, they don’t put him through as much as they used to, but he’s fooling this newcomer, gliding out of his cage and sliding across the wet floor with the ease of a young pup.

Next up, we go to visit Qannik, a seven-year-old beluga whale, whose impressive size isn’t apparent right away with only his head bobbing out of the water. Qannik is one of a handful of belugas who are separated to work with an individual trainer on this morning. Isolating them to work one-on-one helps keep their focus and makes it easier to feed them. While aquarium visitors can watch this training session, the belugas are not currently part of any performance because there is an emphasis on the breeding program. A calf was born at the Shedd last summer, and there is hope for more success in that department.

In the 20 minutes it takes to put Qannik through a leisurely workout of tricks and drills, Tim goes through a huge bucket of herring, which is divided into four layers. It’s all about staying on schedule here, as two other trainers are going through a similar routine with two other whales in the same pool. They constantly communicate with each other as to their progress so they can keep the attention of the animals. Qannik, with his skin shedding, likes a good rub down, not to mention his tongue petted.

I ask Tim if Qannik or another animal would listen or follow directions from an unfamiliar face like, say, me. Tim doesn’t think so. “But that would be a good experiment sometime,” he says. “Animals recognize us, and they learn our patterns and our secrets. They’ve all got personalities too.”

Ordinarily, Tim would take his progress report of the session with Qannik back to the computer and then join the others in chopping up the next meal, but because he’s got a guest on his heels today, pestering him with questions, he gets a reprieve.

and then join the others in chopping up the next meal, but because he’s got a guest on his heels today, pestering him with questions, he gets a reprieve.

Tim saves the best for last. It’s time for the dolphins, but first, a meeting in which the half-dozen trainers involved in the next performance go over their very specific instructions as to how the show will go down. A tail walk by this one, followed by a corkscrew by that one, then a flip by these three and so on. They memorize a 20-minute show in about 45 seconds, and then it’s off to the oceanarium, where hundreds of spectators, most of them kids, eagerly await.

This is where Tim turns into a conductor, directing his assigned dolphin through the show, tossing him fish or offering up a pat on the head or a clap as positive reinforcement. As one of the trainers gets on the microphone to describe the animals and educate the public, the dolphins perform flawlessly, at least from this point of view, with Tim even diving in to swim and direct them from the water at one point. The crowd eats it up.

Around the lunch hour, Tim has to go. He has been more than gracious with his time on what should have been a day off, and now he has family to meet. I, on the other hand, haven’t had enough just yet. Still on a high from being inside the oceanarium with the dolphins, I spend the next two hours ambling through the rest of the Shedd, learning and observing, walking amongst a group of kids a third of my age, feeling like one of them again, pretty certain that Tim Ward does indeed have one of the coolest jobs in the city.

This article was originally published in The Real Chicago in May, 2007.