A day with friends: Spending an afternoon immersed in the vast collections at the Art Institute

By Emily Clement

I went to the Art Institute on a Friday afternoon recently. The front stairs, flanked by the green lions, are filled with people eating and talking. The main lobby, too, is filled with families, groups of friends, and couples.

To avoid the crowds, I duck down the stairs to see the Thorne Miniature Rooms. This gallery has dozens of hyper-detailed, itty-bitty replica rooms from different eras and regions. It’s a favorite among kids.

“Just imagine though!” one boy says to his brother.

“Mom, lookit,” another says, tugging on his mother’s sleeve.

Each room is exquisite and perfect, but my favorite is the French library from the Modern Period. Its balcony has a view of the Eiffel Tower, fully lit. There is even a tiny bottle of Veuve Cliquot on the coffee table.

Next, I head to the Gray Wing. It is remarkably quiet compared to the bustle of the main stairs and lobby. Most people in here are looking at the art alone, and taking their time.

The art in this gallery is changed every few months. I’ve seen everything from propaganda art to practice sketches by some of the masters. Today, it’s a collection of art donated by Eldzier Cortor, a Chicago artist, and a separate collection of mezzotints.

Cortor’s art is striking. My favorite pieces have elongated human figures over geometric designs done in jewel tones. One is of two cerulean dancers; their positions are mirror images, limbs fanned out.

Across the hall from the Gray Wing is the Japanese art. Most of the pieces are ancient treasures, but a set of baskets woven by Fujinuma Noboru were made in the 1970s-90s. Each piece looks simple, but up close proves to be extremely intricate.

The gallery designed by famous Japanese architect Tadao Andō is just the opposite: conspicuous in its simplicity. The darkened room is filled with 16 massive wooden posts arranged in a square and two large benches. The only illumination comes from the lit cases that display painted silk screens and pottery. I am the only one in the gallery. The silence and glowing cases create a peaceful atmosphere.

posts arranged in a square and two large benches. The only illumination comes from the lit cases that display painted silk screens and pottery. I am the only one in the gallery. The silence and glowing cases create a peaceful atmosphere.

Next, I head through the galleries of Asian art. The porcelain pieces of robin’s egg blue and pure white are so pristine it’s hard to believe that some of them are more than 1,100 years old.

A crowd of schoolchildren floods the gallery. They seem to be on a class trip, and a few chaperones and teachers guide them along.

“Everything here is real,” a chaperone assures the students.

I slip past the group into a room with a monumental spiral staircase. There is no art, just the staircase and a giant boulder in the middle of the room. It’s a stark contrast to the rest of the museum. The ceiling is two stories high, and natural light filters through the sheer curtains.

Up the stairs are the European decorative arts. A gray-haired couple fiddles with a tablet in front of an exhibit to learn more about the piece — a 10-foot-tall lacquered door made in Italy in the 1750s.

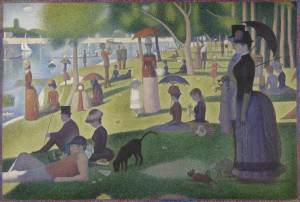

Down a ramp is perhaps the museum’s most famous piece: Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte. A dozen people are gazing at the massive painting Ferris Bueller-style. A middle-aged couple tries a few times to take a selfie in front of the piece. As impressive as the 10 x 6-foot painting is, make sure to check out the tiny studies Seurat did before painting his masterpiece. They are small — less than a foot square — but it is cool to see the artist’s process. And reassuring to know that even masters have rough drafts.

Down a ramp is perhaps the museum’s most famous piece: Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte. A dozen people are gazing at the massive painting Ferris Bueller-style. A middle-aged couple tries a few times to take a selfie in front of the piece. As impressive as the 10 x 6-foot painting is, make sure to check out the tiny studies Seurat did before painting his masterpiece. They are small — less than a foot square — but it is cool to see the artist’s process. And reassuring to know that even masters have rough drafts.

The impressionist galleries are predictably crowded, and understandably so. The Art Institute has one of the best impressionist collections in the world. There is a room filled with just Monets, another with Van Goghs.

A group is seated around At the Moulin Rouge by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec while a docent tells them the scandalous history of the piece. Apparently, the green-faced woman on the right side of the painting was an infamous English singer. She was cut out of the painting to make it easier to sell, but it was later reattached.

After emerging from the galleries, you’re greeted by a huge painting — really almost a mural — by Georgia O’Keefe. Sky Above Clouds IV is situated under a skylight, so at 24 feet wide, it really does give the impression of having just popped above the clouds and into the sunlight on a plane.

The Modern Wing is up next. My first stop is the Architecture Talks Back exhibit. The gallery is filled with offbeat architectural representations. There is a collage featuring photos of a scale model with a scene from the movie Spring Breakers. A video of baby chicks in architectural models runs on a loop. A meticulous model of a skyscraper is topped with an L.E.D. screen that plays anime. A small, unassuming piece seems to be just several kaleidoscopes arranged in a triangle. When you peer through them, though, each one is a window into a different model, complete with tiny people.

In the next room over, another movie screen is set up. This one is of everyday scenes set to classical music. It is strange and mesmerizing. On one side of the room, 25 receipt printers hang from the ceiling. Beneath each is a pile of used paper. Every so often, a printer will chug out a little more paper.

Upon closer inspection, each spool of paper is filled with tweets that have something in common. Each time someone tweets a keyword — empower, architecture, sigh — the printer adds it to the collection.

“How often do they clean this up?” a girl asks one of the guards.

“I don’t think they’re ever gonna clean it up,” he replies. “I think that’s the message.

After nearly three hours in the museum, I’m beginning to feel art fatigue set in. Gunsaulus Hall is the fastest way back to the front entrance, plus its filled with intricate and opulent art from India, Tibet, Nepal, Pakistan and more. Much of it is religious art, some is hundreds of years old.

Before leaving, I head up the grand staircase to see Degas’ paintings and Paris Street; Rainy Day. I think I’ve seen them every time I visit the museum, but they never get dull. By now, they feel like old friends.